Design Review & Critique

Why are design reviews important?

September 18, 2025

I've sat, over the years, in many, many design reviews. One of the most difficult things to learn early on in my career was how to separate design critique from my personal feelings. It's something that quite a decent number of design colleagues and friends & I have discussed.

What I found was that it took effort & training from both sides. All to often, feelings would get hurt, resentment would linger, arguments would occur, and animosity could extend into subsequent reviews.

The catalyst for me, the thing that made me start to examine this more, was almost 20 years ago now at a tech company in the SF Bay area. I was a Senior Interaction Designer on a newly formed team of SR & JR designers, UI developers, and researchers. We were in the process of creating what would eventually become a 'UX Design Team'.

Our team had been formed after an executive moved over as VP of Design. He was well-intentioned & had an interest in design, but zero training or experience. "UX Design" had recently become the new buzzword in Silicon Valley tech and he was caffeinated.

One of the things we implemented as the team grew was to have twice-weekly design reviews. Everyone getting together to share what we were working on and get feedback from each other. On this one particular session, I was one of the presenters.

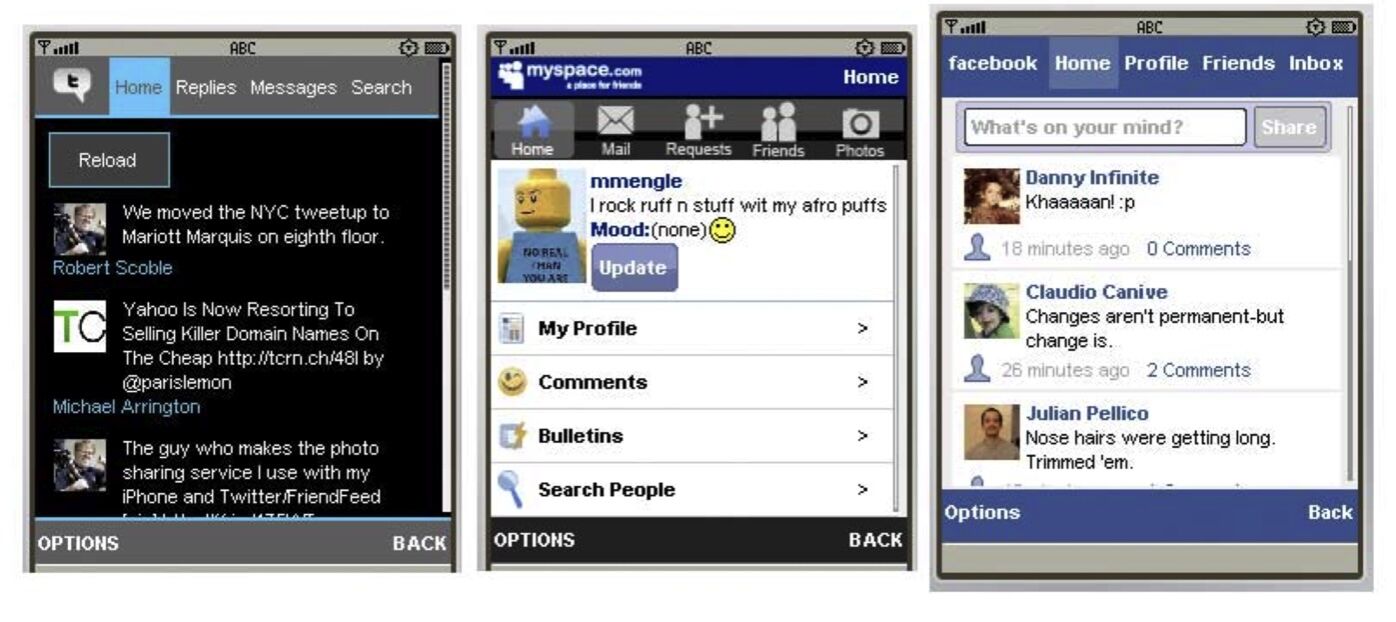

This is early on in the mobile space, when employees were still provided company owned phones, and the app-stores were in their infancy. I’m working on a system for managing what apps were authorized for installation on these devices. It had on-device components and IT backend tools for Mobile Device Management.

So, I finish my presentation, and we’re going around the table, my colleagues sharing insights which we discuss. As it gets to this VP, he says one sentence. “That design is shit.” That’s all. Tells me to try again. No feedback, no insight into what specifically he deemed to be “shit”, nothing helpful or constructive.

I was, shall we say, a bit stunned and very irritated. A jumble of emotions flooded in. Afterward, my other colleagues unanimously had my back. They were just as stunned & angry. That made me feel better, pouring cold water on all of the doubt that crept in. Perhaps the worst part is that the team never respected him again.

Let’s be honest though, your designs being ‘ripped apart’ by your director in the design world wasn’t new to me. Previous critiques from more senior, experienced design leaders, stung & could be brutal, but they always explained where they were coming from, & provided feedback on how to rethink and improve my work. You LEARNED from them.

Some 20 years on, that one instance is still irritating, but it was also a critical lesson for my own leadership.

Design critiques are not (should not be) personal.

Eventually, I would lead and mentor other designers and teams. In every one of my subsequent roles, that moment has been with me. I used its power for good. I used it as a lesson. I always made sure to mentor younger designers, as well as other team members; product managers, developers, marketers.

There is a right and wrong was to critique a design idea and which one you employ begins with the setting of expectations. You need to learn HOW to critique. It is not about ripping a thing apart, or “scoring points”.

About 10 years ago, I put together a presentation.

It was pretty simple. I still use it today. I begin by telling that story. The story of the leader who didn’t know how to lead.

Here it is. I always started this presentation by asking about the title image. Surprisingly some didn’t get it.

Design Review & Critique

Why are design reviews important?

Critiques are meant to improve output, rather than hinder progress. Collaboration and feedback improves your work. The designer who owns the design should own the critique session. Reviews should be conducted early and often in the process.

Proper feedback can reveal critical design flaws. Proper feedback lets you know if you're on the right track.

Presenter

The person who owns the design. Explain what you are showing, convey what you have done, and be clear about where you need help. Communicate what stage you are at in the process. Walk through your rationale. Provide context. Accept any feedback graciously & thoughtfully. The commentary is (should be) on the work, NOT you. Take notes during the feedback.

Moderator

Have a Moderator to help keep people focused and make sure the presenter has a successful critique. They should make sure the feedback doesn’t veer away from the presenter’s scope; be a time-keeper. The moderator sends anything requiring deeper discussion to a ‘parking lot’. Explain that questions should be held/written down until the end.

Reviewers

Those critiquing the design. Ask yourself, ‘How can I help this person improve their work?’ Hold your questions until the presenter is done, unless it is a clarifying question. Write down any feedback you think of. Frame it for understanding and action. Your feedback should be useful. Speak about the design NOT the designer. Avoid the pronoun ‘you’. Understand what they have done. See the opportunities to improve. Be specific about what is working and what is not. Speak from the target-customer-user’s perspective. YOU are not the user.

That’s pretty much it. What have you done? How have you handled difficult situations. What feedback do you have for me on this subject?

Here’s a link to the PDF of my presentation — feel fee to use. Download